Scientists develop new material that captures CO2 and turns it into “useful organic chemicals”

10/28/2020 / By Virgilio Marin

Researchers from Japan and China have developed a new material that can suck carbon dioxide out of the air and convert it into organic matter. The material works as a “molecular” sieve and selectively captures carbon dioxide molecules

As reported in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications, carbon dioxide that’s caught in the material can be transformed into an organic substance that can be used in petrochemicals.

Recyclable material captures carbon dioxide

Though there are existing methods of capturing and sequestering carbon dioxide, these methods consume a lot of energy. Carbon dioxide has low reactivity, so it requires a lot of energy to be captured and converted into a new substance.

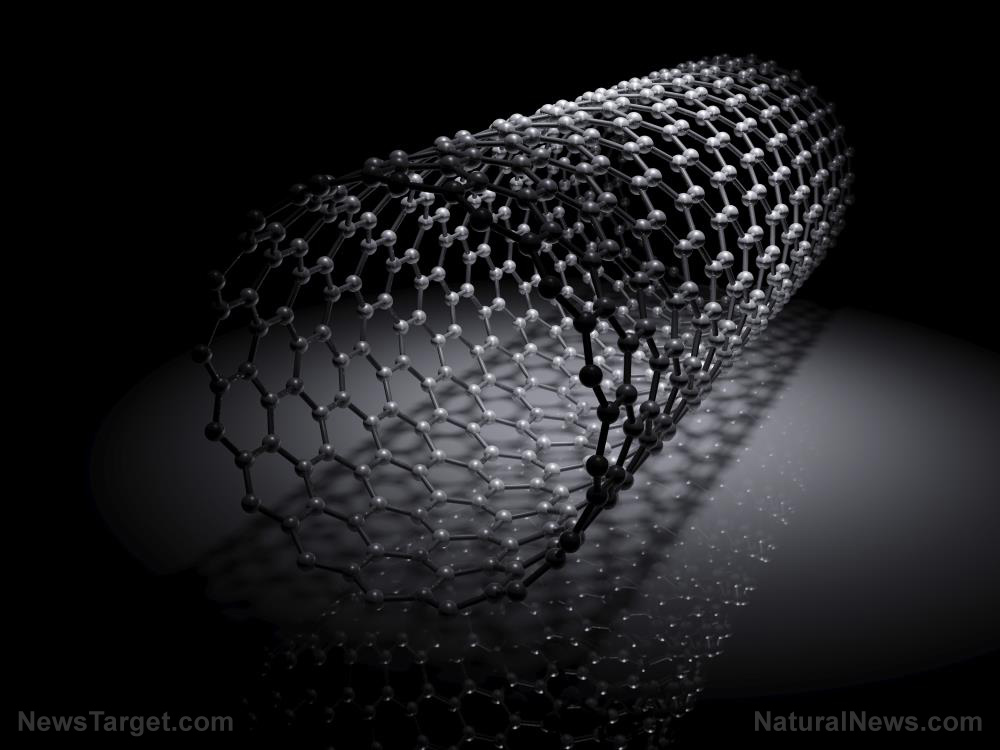

To solve this problem, the researchers developed a porous coordination polymer (PCP) – a metal-organic framework made of metal ions – made out of zinc ions. The resulting material was highly porous and has a high affinity to carbon dioxide molecules, according to co-author Ken-ichi Otake of the Kyoto University Institute for Advanced Study in Japan.

The key ingredient, the researchers said, was an organic component with a propeller-like molecular structure. As carbon dioxide molecules approach the material, the structure rotates and rearranges, allowing the molecules to get trapped. This is because the material recognizes molecules by shape and size, selectively capturing carbon dioxide.

When the researchers tested the new material, they found that it captured carbon dioxide molecules with 10 times the efficiency of other PCPs. What’s more, the material promises to be reusable as its efficiency did not decrease even after 10 reaction cycles.

The trapped carbon dioxide, on the other hand, is converted into organic chemicals like cyclic carbonates. These compounds are commonly used as additives in fuels and electrolytes in batteries. Meanwhile, the PCP can be recycled to make polyurethane, a versatile material used in clothing, domestic appliances, packaging and several other applications.

More carbon capture technologies

In another study published in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, Swedish researchers developed a carbon capture foam made of cellulose, gelatin and zeolite – a non-toxic, highly porous mineral whose excellent adsorbing properties effectively trap carbon dioxide molecules.

But while zeolite seems to be the perfect material for capturing carbon, it’s actually difficult to process and implement in different applications due to its relatively large particles. So for the study, the researchers prepared zeolite differently – as smaller particles in suspension. This way, the mineral could easily be incorporated into highly porous cellulose foam.

“The cellulose and zeolites together therefore create an environmentally friendly, affordable material,” said co-author Walter Rosas of the at Chalmers University of Technology’s Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering.

The leading carbon capture method today uses amines suspended in a solution. Amines, however, are not environmentally friendly as the solution corrodes pipes and tanks. Moreover, a lot of energy is required to separate the trapped carbon dioxide from the amine solution before the latter can be reused. (Related: California’s redwood forests capture massive amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide.)

The new material, according to the researchers, does away with all of these problems. For one, the foam is a solid, which means it’s easier to separate the carbon dioxide molecules from the foam. It’s also lightweight; the researchers placed it on top of a flower, and the flower’s filaments did not budge at the weight of the foam.

As research on carbon sequestration becomes increasingly popular, these two studies pave the way for the further development of sustainable carbon capture technology and open up new avenues for future research.

CarbonDioxide.news has more on the latest carbon capture technologies.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: amines, Carbon capture, carbon dioxide, carbon sequestration, eco-friendly, eco-friendly tech, environment, goodtech, porous coordination polymer, zeolite

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FUTURE SCIENCE NEWS