3D-printed generator allows you to generate electricity from snowfall

11/08/2019 / By Edsel Cook

People can now tap snowfall for electricity, thanks to triboelectric nanogenerators that collect electrical energy from innocuous activities like footsteps and raindrops. The new energy harvester, developed by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), is not only inexpensive but light as well – matching the thinness and flexibility of a plastic sheet.

“The device can work in remote areas because it provides its own power and does not need batteries,” explained UCLA researcher Richard Kaner, the senior author of the study. “It’s a very clever device – a weather station that can tell you how much snow is falling, the direction the snow is falling, and the direction and speed of the wind.”

Like its conventional counterparts, the “snow-based triboelectric nanogenerator” draws electrical charge from static electricity. It takes advantage of the transfer of electrons to produce usable energy.

Kaner and his team released the details of their nanogenerator on the journal Nano Energy.

In a statement, Kaner explained how the interplay between materials that attract electrons and other substances that released the same particles produced static electricity. By separating these electric charges, a triboelectric generator produces electricity from scratch. (Related: Harnessing static electricity? Invention makes self-powered devices possible, without batteries.)

This tiny generator produces electricity from snow

Snow naturally possesses a positive charge – as such, it gives up electrons. In the study, the UCLA researchers looked for a negatively charged material to take advantage of those properties. They settled upon silicone, a rubbery artificial compound made from silicon and oxygen atoms, as well as carbon and hydrogen.

When snow falls on the surface of silicone, the physical contact causes electrons to leave the former and flow to the latter. The resulting charge is captured by the snow-based triboelectric generator, which turns it into electricity.

UCLA researcher and co-author Maher El-Kady explained that snow possesses an electrical charge: If the substance comes into contact with another material with the opposite charge, it becomes possible to extract the energy and turn it into electricity.

“While snow likes to give up electrons, the performance of the device depends on the efficiency of the other material at extracting these electrons,” explained El-Kady. “After testing a large number of materials including aluminum foils and Teflon, we found that silicone produces more charge than any other material.”

Various possible uses for snow-based triboelectric nanogenerators

Every year, snow blankets roughly 30 percent of the planet. This means that solar panels in regions that experience winter season operate at a much lower efficiency. When snow piles up on a photovoltaic array, it blocks off much of the sunlight. The obstructed solar cell produces less power, making it less effective at powering a home or building.

El-Kady suggested adding the snow-based triboelectric nanogenerator to the surface of a solar panel. The layer is thin enough to permit the passage of sunlight during sunny periods. More importantly, it makes it possible for the cell to continue generating electricity despite being covered in snow.

The nanogenerator may also keep track of a winter sports athlete, especially during jumps, runs, and walks. Unlike a smartwatch, it may recognize the primary patterns of movement during cross-country skiing.

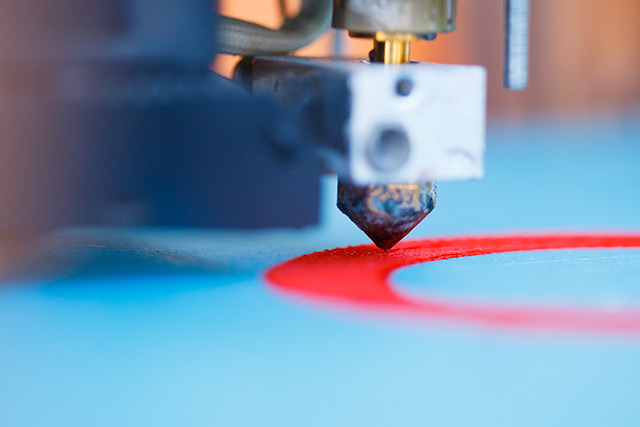

The snow-powered triboelectric nanogenerator consisted of a silicone layer and an electrode that gathered the charge. The prototype was produced with a 3D printer.

The UCLA team said that they might manufacture the device with ease and at a low cost. Silicone is cheap, easy to obtain, and used in a variety of roles such as insulation for electrical wires, lubricating substances, and biomedical devices. It may now harness energy from the snow.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: 3D printing, electricity, gadgets and devices, goodtechnology, innovations, inventions, silicone, snow, solar panels, static electricity, sustainable energy, triboelectric nanogenerators, wearable electronics

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FUTURE SCIENCE NEWS